Every second, bacteriophages viruses that infect bacteria destroy an estimated 10^23 bacterial cells, quietly shaping ecosystems, food safety, and medicine. In a milliliter of seawater, you can find roughly 10 million phage particles; in a hospital, a carefully chosen phage cocktail can salvage an infection that antibiotics cannot touch.

If you came here asking, “What is a bacteriophage,” the concise answer is: a virus specialized to invade bacteria. Below is a fast, evidence-based tour of how phages work, why they dominate microbial life, where they already matter in practice, and the limits that still constrain them.

What Bacteriophages Are And How They Work

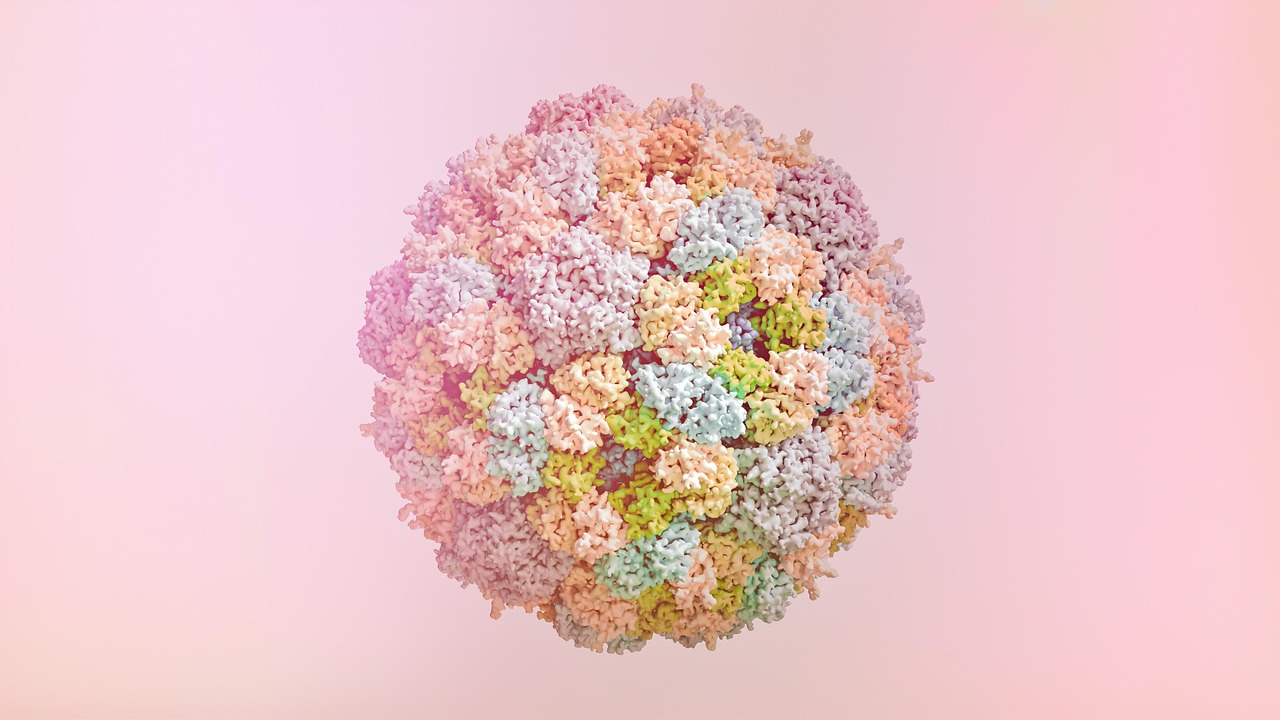

A bacteriophage (phage) is a virus that targets bacteria with narrow specificity. Most are 50–200 nanometers across and consist of a protein capsid that encloses DNA or RNA (commonly 5–500 kilobases), often with a tail that recognizes bacterial receptors. Tailed phages (class Caudoviricetes) dominate known phage diversity. Host range is determined largely by tail fibers or receptor-binding proteins that latch onto bacterial surface molecules such as lipopolysaccharides, teichoic acids, or porins.

Phage infection typically follows a sequence: adsorption to a surface receptor, genome injection, replication using bacterial machinery, assembly, and cell lysis. In optimal lab conditions, a single infected cell can release 50–200 progeny (the “burst size”) after a 20–60 minute latent period. Specificity cuts both ways: it allows precise targeting but means a phage that kills one strain of Pseudomonas may not affect a closely related strain living in the same wound.

Lytic Versus Temperate Cycles

Lytic phages replicate and promptly lyse host cells. Temperate phages can integrate into the bacterial genome (a prophage) and lie dormant, replicating with the host until stress UV exposure, DNA damage, or some antibiotics triggers induction and lysis. Prophages often carry accessory genes that change bacterial behavior; notorious examples include cholera toxin and diphtheria toxin encoded by prophages. For therapy, strictly lytic phages are preferred to avoid gene transfer risks.

Bacteria fight back. Restriction–modification systems cut foreign DNA; CRISPR–Cas records snippets of invaders and targets them upon re-encounter; abortive infection systems sacrifice an infected cell to protect the population. Phages counter with anti-CRISPR proteins, modified bases that evade restriction enzymes, and receptor-switching. The arms race is fast: generation times under an hour enable rapid coevolution.

Ecology And Evolutionary Impact

Phages are the most abundant biological entities on Earth roughly 10^31 particles. In marine systems, viral lysis is estimated to remove 20–40% of bacterial biomass daily, short-circuiting the food web through the “viral shunt”: nutrients locked in cells are recycled as dissolved organic matter. This recycling influences global carbon fluxes, affecting how much carbon sinks into the deep ocean versus remains in surface waters.

Phages help maintain microbial diversity via “kill-the-winner” dynamics. When one bacterial lineage blooms, its specific phages expand, suppressing the dominant strain and allowing competitors to persist. This predator–prey feedback yields oscillations that stabilize communities and can change with temperature, nutrient levels, and salinity. Even subtle receptor changes on bacterial surfaces can reshape which phage–host pairs thrive.

Phages are vectors of horizontal gene transfer through generalized and specialized transduction. That mobility reshapes pathogens: Shiga toxin in E. coli O157:H7 and cholera toxin in Vibrio cholerae are prophage-encoded. Clinical relevance is immediate: antibiotics that induce DNA damage can also induce prophages, potentially elevating toxin production an argument for choosing therapies that minimize induction in toxin-mediated disease.

In humans, the gut virome may contain 10^8–10^9 virus-like particles per gram of feces, dominated by phages. Diet shifts, antibiotics, and infections can rebalance which phages and bacteria coexist. Early studies of “fecal virome transfer” as a therapy for recurrent Clostridioides difficile suggest potential, but controlled evidence is limited and mechanisms are not fully resolved.

Phage Therapy And Biotechnology

Phage therapy predates antibiotics and persisted in parts of Eastern Europe when the West abandoned it. The modern resurgence is driven by multidrug-resistant infections. Compassionate-use cases have cleared otherwise intractable Pseudomonas, Mycobacterium abscessus, and Acinetobacter infections, especially in prosthetic devices and cystic fibrosis. Evidence from controlled trials remains limited; the PhagoBurn randomized trial in burn patients underperformed standard care, primarily due to underdosing the phage concentration fell orders of magnitude below the planned 10^8 plaque-forming units (PFU)/mL during storage.

Practical therapy usually follows a “phagogram” workflow. The pathogen is isolated, screened against a library of candidate phages, and a cocktail of two to ten active, strictly lytic phages is formulated. Doses often target 10^8–10^10 PFU per administration by route appropriate to the infection: topical for wounds, inhaled for airway disease, intravesical for urinary tract, or intravenous for disseminated infections. Treatment typically spans days to weeks. Combining phages with antibiotics can be synergistic: sub-inhibitory antibiotics may expose receptors or slow resistance, while phages can select for bacterial mutations that trade resistance for reduced virulence or increased antibiotic susceptibility.

Safety has been favorable in most reports, but there are real constraints. Intravenous preparations must meet tight endotoxin limits (for many drugs, roughly 5 endotoxin units per kilogram per hour) to avoid fevers or shock. Manufacturing must ensure sterility, stable titers, and fully sequenced genomes free of toxin or antibiotic-resistance genes. The mononuclear phagocyte system clears circulating phages with half-lives ranging from minutes to hours, so repeated dosing or localized delivery is often necessary. Immune neutralization can develop over multiweek courses, which may require phage rotation.

Beyond therapy, phages are already in commerce. Several food-safety phage products reduce Listeria, Salmonella, or E. coli O157 contamination on ready-to-eat foods without altering taste. Reporter phages that carry luminescent genes detect live bacteria in hours rather than days, useful for Mycobacterium or Listeria screening. Phage display often using filamentous M13 screens peptide or antibody libraries of 10^9 variants to discover binders for diagnostics, therapeutics, and vaccine design.

Constraints, Risks, And Practical Realities

Precision cuts both ways. A narrow host range means a perfect match can be potent, but a mismatched phage is inert. In polymicrobial infections, multiple strains and biofilms complicate targeting. Biofilms impede diffusion; some phages naturally carry depolymerases that digest extracellular polysaccharides, but others require engineering or adjuvants. Effective treatment often demands high local multiplicity of infection, achieved by direct application to catheters, wound beds, or airway surfaces.

Resistance emerges quickly. Bacteria may alter or mask receptors, upregulate CRISPR–Cas, or deploy abortive infection. Countermeasures include cocktails that target distinct receptors, sequential phage rotation, and combination therapy where antibiotics and phages push bacteria into evolutionary dead-ends. In some systems, phage pressure drives bacteria to shed capsules or efflux pumps, making them less virulent or more antibiotic-susceptible a trade-off clinicians can exploit.

Regulation and manufacturing are nontrivial. Fixed, off-the-shelf cocktails are simpler to license but risk obsolescence as bacteria evolve. Personalized phage therapy selecting or adapting phages for a patient’s isolate requires rapid screening, sequencing, and GMP manufacturing on clinically relevant timelines. Quality control includes whole-genome sequencing to exclude lysogeny and virulence genes, sterility testing, endotoxin quantification, and activity assays. Titers can fall during storage depending on buffer and temperature, so stability studies matter as much as initial potency.

Ecologically, releasing phages is not unprecedented phages are already everywhere but deliberate application can still shift local gene flow. Generalized transduction can move bacterial DNA, and temperate phages can mobilize toxins. Choosing strictly lytic phages with clean genomes, minimizing induction risks, and monitoring for resistance and gene transfer are practical guardrails.

Conclusion

If your core question is “What is a bacteriophage,” think of it as a precision predator of bacteria with industrial-scale presence and clinical potential. For public health and clinics: start with lytic phages screened against a confirmed isolate, aim for high titers and local delivery when possible, pair with antibiotics for synergy, and sequence for safety. For policymakers and labs: invest in curated phage banks, fast phagograms, and GMP capacity. For everyone else: expect phages to remain invisible but consequential, from oceans to operating rooms.